"Medical Affairs in the Heart of the Arctics"', by N. Senn, MD

The geographic distribution of disease, the study of primitive races, of their climatic conditions, customs, habits and manner of living as etiologic influences, their methods employed in combatting disease and their resources in the treatment of accidents are subjects which can not fail to interest physicians who are concerned in the progress of their profession and the welfare of humanity the world over.

|

| Greenland, image source, wiki |

|

| Peary in Arctic furs, image source, wiki |

|

| Cape York, image source, wiki |

THE REAL ESKIMOS.

|

| an eskimo of mixed race |

|

| pure-blood Eskimos |

Commander Peary has been among these people a good deal of his time for the last 14 years. He knows them well, can call them by their names and has their unlimited confidence. He knows the history of all of them who are more than 2 years of age. He speaks their language and is perfectly familiar with their habits of life and the few diseases to which they have been subject since he first visited them. He is a very careful observer and his statements can be relied on.

|

| eskimo woman |

The Eskimos are the filthiest people in the world. They never wash, not even the face and hands. The smell of the fur clothing and secretions of the skin are productive of a stench about their persons and especially in their igloos and tents that is characteristic and at first very obnoxious to the uninitiated. During winter these people live in huts (igloos) (Figs. 4 and 5). of stone or ice; in summer in tents of sealskin. Furs are used for the common family bed and each occupant, from father to babe, strips completely before retiring. They do not marry in the sense in which we use this word, but mate like animals for convenient periods of time, which may be for life, for a year, or only for a hunting trip of a few days. Exchange of mates for an indefinite time is of common occurrence.

|

| stone igloo |

These people are all children, contented, peaceable, honest and hospitable; they are without a ruler and without any ambition for fame or power—an ideal socialistic community where property is held in common, politics unknown, and where all are on the same social plane.

They subsist almost exclusively on a raw animal diet, which explains the absence of a number of diseases that are common among the civilized people. Salt water contains iodin, and all animals living in it and all animals which live on sea food absorb more or less of this fickle chemical substance. None of these people has ever suffered from scurvy, which was such a common affection among the crews of the early polar expeditions and which occasionally afflicts the Eskimos who consume more cooked than raw animal food. Peary has profited by this observation, and places great importance in supplying his crew with fresh meat, and has never seen a case of scurvy among them. He has found by experience that lime juice, which formerly enjoyed such an enviable reputation as an antiscorbutic, is not only useless but harmful. Taken in the Arctic region, it acts as a cathartic and becomes distasteful to those who have used it.

|

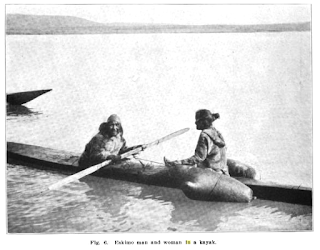

| eskimo man and woman in a kayak |

Although I have no positive information on the subject, I am satisfied that the exclusion of all vegetable food from the diet has shortened the gastrointestinal canal, that the appendix, if present at all, is in the most rudimentary form and that the glands concerned in the digestion of starchy food have become atrophic, while those whose secretion is needed for the digestion of meat and the emulsification of the fats are hypertrophic. The stomach digestion of these people is something wonderful. Indigestion is about as infrequent as in the dog— in fact I believe there is the closest analogy between the anatomy and physiology of the organs of digestion of the Eskimo and the only domestic animal with which he is familiar, the dog. Commander Peary and a number of the men of both crews, who have seen much of Eskimo life, can not remember of ever having seen a case of chronic indigestion, peritonitis, or intestinal obstruction. Hair and fragments of bone taken with the food by the dog occasionally produce peritonitis in this animal, but these mechanical causes for such affections of the intestinal canal are excluded from the diet of the Eskimo. We would naturally conclude that an exclusive animal diet would cause constipation and a uric acid diathesis with a long train of their remote consequences —headache, insomnia, skin eruptions, gout, rheumatism, etc.—but this is not the case. The large percentage of oil contained in their diet acts as a gentle laxative and protects them against a multitude of ailments which form the major part of the diseases with which the general practitioner has to deal. The Eskimo can eat with relish and without any ill consequences old, stinking blubber that would turn the stomach of a crow and that if eaten by a white man, if he could retain it, would kill him by producing ptomain poisoning.

The skin of the Eskimo, covered with filth and vermin, is remarkable for its smoothness and immunity to skin diseases. The only skin eruptions I have seen among the large number of Eskimos of all ages I examined was a patch of psoriasis over the posterior surface of the elbow of a syphilitic, and a small pustular eruption affecting one ala of the nose in an infant suffering from a nasal catarrh. The very fact that these people fear and avoid the external use of water may account for their freedom from diseases of the skin. The exposure of the hair to the midnight sun for more than throe months of the year and the wearing of a loose hood of fur during the winter favors hair growth. Baldness is unknown here and even Time finds it difficult to bleach the coal-black hair and beard. Men and women of 6O and more years show only here and there a gray streak in the luxuriant hair never touched by the comb.

The special senses, except that of smell, are very keen and old age appears to have little if any influence in diminishing the acuteness of sight and hearing. The acuteness of vision for near and distant objects of these people is something that will astonish the visitor. I became aware of this on my hunting trips under the guidance of Eskimos. They could see a hare or a bird far beyond the reach of my vision and could calculate the distance with an infallible accuracy, something no one is capable of doing who is not habituated to the rarity of the atmosphere of the Arctic region.

DISEASES.

It would take much less space to enumerate the diseases to which the Eskimos are subject than to name those to which they appear to be almost immune so long as they live in their own climate and do not deviate from their customary habits of life.

Tuberculosis in any form is unknown among the Eskimos in the heart of the Arctic region. I heard no phthisical cough, saw no emaciated forms nor hectic flush; no cases of lupus, glandular, joint or bone tuberculosis and no cripples except the man who lost part of one foot from frost bite. Experience, however, has shown that as soon as these people are brought to the United States they contract pulmonary tuberculosis of the most virulent form and succumb to the disease in a few months. Of six persons brought to the American Museum of Natural History in New York all contracted the disease and in less than six months four of them were dead, one returned and recovered and one remained in New York still suffering from a more lingering form of the disease. The one who returned to his Arctic home and resumed his former manner of living made a very speedy and permanent recovery, a strong argument in favor of the Arctic region as a summer resort for tubercular patients. The focus of infection created by this patient in the settlement to which he came and where he has since lived has proved harmless during the eight years that have expired since his return.

Rheumatism is one of the most prevalent diseases among the Eskimos. At the North Star Bay settlement I found a man about 35 years of age in one of the tents completely crippled by this disease which, according to Peary, commenced twelve years before. He was lying helpless on his reindeer skin, with every large joint of all the limbs contracted and stiff. The left elbow was swollen, painful and exquisitely tender to the slightest touch. He was smoking and appeared to be not in the least concerned about his helpless condition, as, according to the prevailing custom among the natives, the tribe provided him and his family with food and clothing. Lumbago and sciatica frequently affect in this climate the crews of expeditions and whalers.

Venereal diseases were introduced here by the whites and have become widely diffused throughout the native population, owing to the unrestrained, promiscuous intercourse practiced everywhere. Syphilis pursues a very mild course in the natives. None of the terrible ravages of the tertiary form of this disease, with which we are so familiar, are seen here. I have no doubt that the iodin contained in their food furnishes a satisfactory explanation for this. A well-known Eskimo is known to have contracted the disease eight years ago. He has had no treatment of any kind and is now in perfect health and the father of several healthy, vigorous children. I examined a boy about 15 years of age who was then the subject of secondary lesions. I found mucus patches on the inner surface of the lower lip, general lymphatic hyperplasia but no cutaneous eruptions. The severest case of tertiary syphilis I have seen was in the case of a man about 50 years of age whose woman was infected by a member of an Arctic crew some eight or ten years ago. One of her children of a corresponding age, a girl, is a half-caste, pale and delicate. This man bore all the marks of a syphilitic cachexia; his arteries were atheromatous, a patch of psoriasis affected the posterior aspect of one of the elbow joints and the cervical and epitrochlear glands were very much enlarged. I did not see a single case of saddle-nose, of gumma, periostitis, Hutchinson's teeth or syphilitic alopecia. These facts prove conclusively that syphilis among these people pursues an unusually benign course, for which we must give credit to Iheir liberally iodized sea food. Gonorrhea seems to follow the same benign course. Careful inquiry and abundant testimony from reliable sources combine to show that stricture, orchitis and cystitis do not exist. I questioned Commander Peary and Mr. Henson, his main man, who have spent seven winters among these natives, with special reference to the existence of urinary difficulties among old men. From their accounts it appears that prostatic obstruction does not exist, as they have seen many of the men urinate, and noticed that the stream was large and strong. The sexua| life of these people and the iodized food may account for the absence of senile prostatic hypertrophy and its consequences, urinary obstruction and eventually renal disease. I saw one case of gonorrheal ophthalmia of a mild form in an adult and complete corneal opacity of one eye in the case of a young girl, caused undoubtedly by this disease. One man and a woman had each lost an eye from traumatic causes.

|

| Marie Peary, born 1893. aaaawwwww:) |

Animal life during this time receives the same stimulating benefit from the sun.

Affections of the Nervous System.—Insanity among the Eskimos is unknown. As these people have never been given an opportunity to indulge in alcoholic drinks they are free from all affections due to alcoholism. Smoking is a new vice with them which crept in a few years ago, but as the supply of tobacco is irregular and most of the time scanty or entirely lacking, it has so far produced no ill results. The natives, howrever, have a strong liking for the weed and when the supply of tobacco warrants it, young and old enjoy the pipe, which makes its rounds if only one is at their disposal. I have seen children on their mothers' backs do their good share in burning up the contents of a pipe. The same causes which combine in the causation of winter anemia result occasionally in producing a nervous condition closely allied to, if not identical with, hysteria. Peary in 1900, on his trip to the northeast coast of Greenland, witnessed this condition and describes it as follows: "When we were drinking our tea one of the younger Eskimos fell in a fit and the others became hysterical. I felt a peculiar dizzy sensation myself. Recognizing the effect of our alcohol cooker in the close atmosphere of the igloo, with every aperture sealed by the newly-fallen snow, I hurriedly kicked out the door and a portion of the front wall. This relieved matters, and I sent three of the Eskimos outside to get the benefit of the fresh air, while I took the two worst ones in hand personally, and finally succeeded in quieting them down. After this they were 'ankooting' all day. The open water ahead of as, the groaning pack beside us, the bad weather and the, to them, mysterious attack of the morning, had combined to put them all in a very timid and unsteady frame of mind" (McClure's Magazine).

It is well known that the long winter, with its depressing effects on body and mind, often disturbs the equilibrium of the otherwise well-balanced nervous system of the natives. But the nervousness, or call it hysteria, never becomes chronic, and disappears under more favorable climatic or dietetic conditions. A similar train of nervous symptoms has not infrequently been observed in members of Arctic expeditions who wintered here and the depression in one or two cases has been so grave as to induce the poor sufferers to seek relief by committing suicide. I could not learn of a single case of epilepsy, chorea or apoplexy.

|

| Peary in 1909, image source, wiki commons |