Instead of banning OxyContin, the DEA is banning a harmless substitute.

t’s not every day a drug kingpin makes Forbes magazine’s “Most Powerful People” list. But thanks to power generated by total domination of illegal narcotic sales, that’s exactly where Joaquín “Chapo” Guzman found himself in 2013, when Forbes ranked him the 67th most powerful man on a planet of 7.1 billion people.

Under Guzman’s direction, the Sinaloa Cartel has taken control of 30 percent of the United States heroin market, bringing in between $3 and 4 billion annually. That’s billion with a “B.” Chapo’s net worth is estimated to be $1 billion, putting him just below Oprah and somewhere north of Paul McCartney.

So how did we get here?

It all changed in the 1980s, really. As it turns out, Americans really liked cocaine, and to understand the modern day heroin trade, you have to understand the evolution of Mexican cocaine smuggling.

According to the Center for Latin American Studies at the University of Miami, cocaine imports increased more than 1000 percent during the 1980s. As America’s appetite for cocaine grew, the Colombians were there to keep us well fed. Their preferred method of smuggling was through the Caribbean, but the United States government shut down that corridor.

Consequently, the Colombians started moving their product across Mexico, with Mexican gangs acting primarily as middlemen smugglers. When Colombian and Peruvian cartels began paying the Mexicans in cocaine rather than cash for their services, the entire balance of power shifted from Central and South America to Mexico.

El Chapo cut his teeth with the Guadalajara Cartel, where he fell into favor with the cartel’s founder, Miguel Gallardo, known as El Padrino (The Godfather). Gallardo controlled nearly every smuggling corridor between Mexico and the United States, delegating control over those corridors to various lieutenants, known as capos. It was here where Chapo Guzman learned how to really sell drugs.

There is a very long list of things you can do in Mexico — and only Mexico — and get away with it for the right price. Unfortunately for El Padrino, murdering an undercover US DEA agent is not on that list. Gallardo’s arrest in 1989 fractured the leadership of the cartel. Guzman found himself in possession of Gallardo’s Pacific Corridor or, as it’s known today, the new Sinaloa Cartel.

________________________________________

It’s not every day a drug manufacturer makes the Forbes list of “America’s Richest Families” on the back of the legal narcotics market. But when you’re the one holding the patent on OxyContin — a drug Americans seemingly can’t get enough of — well, you might just find yourself the sixteenth most wealthy family on a planet of 7.1 billion people.

Meet the Sackler family.

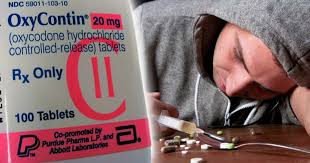

Family owned and operated, Purdue Pharma struck narcotic gold. Not many companies can boast a product whose sales increased 2000 percent in five years, but the Sacklers can do just that. In 1995, the year after receiving FDA approval, OxyContin accounted for $45 million in sales. By 2000, sales increased to $1.4 billion.

Once again, that’s billion with a “B.”

In 2010, thanks to the efforts of three brothers from Brooklyn, OxyContin took control of 30 percent of the United States painkiller market, accounting for $3.1 billion in sales.

So how did we get here?

Born in 1913, Arthur Sackler graduated from the New York School of Medicine and became a medicinal renaissance man, simultaneously mastering psychiatric research and pharmaceutical marketing. In 1942, Arthur bought into Williams, Douglas & McAdams, a New York advertising firm. It was here where Arthur Sackler learned how to really sell drugs.

The 1940s saw the explosion onto the scene of antibiotics and antibacterials, and every time one was created, a new, “better” one was close behind. Pharmaceuticals had entered a new era. Quinine and chloroquine for malaria, streptomycin for tuberculosis, DDT for plague. New drugs were abundant, and Arthur Sackler devoted his time and energy to finding new ways to get those drugs into the hands of patients. He was one of the first to realize the marketing potential of medical journals, widely read by physicians, to influence prescribing patterns. Sackler also began experimenting with advertising on television and radio. This idea of convincing doctors to prescribe your drug was revolutionary at the time.

While Sackler used his background in psychiatric research to tinker with the minds of doctors, his two brothers were embarking upon their own adventure. In 1952, brothers Raymond and Mortimer Sackler bought a small, fledgling pharmaceutical company called Purdue, Frederick, and Co., whose best sellers were things like laxatives and antiseptics. While Raymond and Mortimer learned how to run Purdue, Frederick, and Co. on the fly, Arthur Sackler was busy changing the pharmaceutical marketing world.

Thanks to Arthur’s efforts, Valium became the first drug to hit $100 million in profit. Finding new, off-label uses for the drug, Sackler was able to convince doctors to prescribe Valium and Librium for things not approved in their original FDA application. The Medical Advertising Hall of Fame — yes, such a thing really exists— celebrates Arthur’s ingenuity and his ability to “position different indications for … Librium and Valium.”

After mastering the art of pharmaceutical marketing, Arthur bought into Purdue, Frederick, and Co., and passed along to his brothers everything he knew about selling drugs. By the time Arthur passed away in 1987, Raymond and Mortimer had learned as much as they needed to learn from their brother. While Purdue, Frederick, and Co. had made a decent profit over the years, it was anything but an industry leader.

That was about to change.

Raymond and Mortimer used their medical training to take oxycodone, a drug that was created in Germany in 1917, and tweak it just a bit, creating a tablet with higher potency but designed as an “ER” or “extended release,” where the medication is absorbed into the bloodstream slowly thanks to a plastic coating around the pill.

But they knew the creation of the drug was only half of the equation. After all, what good is a new medication if doctors aren’t prescribing it? Using the knowledge acquired from their brother Arthur, Raymond and Mortimer set out to change the painkiller game. Eight years after Arthur’s death, Purdue submitted their application to the FDA for a new drug called OxyContin.

________________________________________

In Mexico, when you attempt to buy government favors, it’s called bribery.

When it came to dealing with the United States, it worked like this: the drugs were on this side of the border. The addicts were on that side of the border. And in between? The Mexican government, an obstacle that could be leased with an option to buy if you knew people who knew people.

Guzman’s mentor, Miguel “El Padrino” Gallardo, taught him many things, the most important of which was how to make friends in high places. The CIA, FBI, DEA — it didn’t matter. When it came to the government, you didn’t fight them. You joined them.

For the right price, of course.

Guzman, a cool combination of sinister and pragmatic, had the foresight to understand he didn’t need to fight the system. He could rig the system and make it work for him.

These agencies, Guzman understood, were all about the photo-op. Appearances. The big bust, the big pile of drugs on the table, the big stacks of money in the background, the smiling agents posing with packages of white powder.

Guzman was responsible for many government photo-ops, ratting out locations of rival cartels’ leaders to the US feds, and keeping his competitors perpetually on the run.

What Guzman got for cooperating with the Feds is up for debate. What isn’t up for debate, however, is the fact Chapo Guzman escaped two separate maximum security prison, both times under very dubious circumstances.

After his first prison escape in 2001, Chapo took a look around. The drug game was different. Things had changed. Since his prison sentence had begun in 1993, cocaine sales were down as the US demand for the drug had decreased. America’s “War on Drugs” had come down particularly hard on inner cities, cutting heavily into the cocaine sales that once supplied the American crack epidemic of the 1980s.

However, something else was happening north of the border in 2001, something quite curious. Heroin, the use of which had been on a steady decline in the US since the 1960s, was suddenly in high demand throughout the late 90s, seemingly out of nowhere. Somehow, heroin — always a valuable product for the Sinaloa, but in limited quantities due to limited demand — was making a comeback in the United States. Not only was it making a comeback, but there was a sudden demand for opiates among demographics that didn’t traditionally use the drug. Wealthy white kids in college towns were getting hooked. America saw this as a crisis, but Guzman saw it as an opportunity.

Using innovative and anticipatory thinking that in another life would have had him running a Fortune 500 company, Chapo got to work. In a shrewd yet brilliant business move, Guzman and the Sinaloa spent the next decade dumping resources into opium poppy cultivation and heroin refineries.

If the Americans were going to demand heroin, Chapo Guzman would be the one to supply it.

________________________________________

In America, when you attempt to buy government favors, it’s called lobbying.

When it came to the pharmaceutical industry, it worked like this: newly approved FDA drugs were over here. Potential users of the drug were over there. In between? Bureaucrats, medical boards, and elected officials whose votes could potentially be swayed — for a substantial donation, of course — if you knew people who knew people.

In the early 90s, the painkiller industry was stagnant, as it had been in the 80s, as it had been in the 70s. There wasn’t a whole lot of money to be made producing opioid painkillers since they were primarily used to treat cancer patients and people just out of surgery. And, well, to be frank, only so many people get cancer, and only so many people have surgery.

Sure, opioids made a profit for the pharmaceutical industry, but in limited quantities due to a limited demand.

The solution? Simple. Manufacture a demand. Establish not only a new system that gives doctors more freedom to prescribe narcotics for non-postoperative and non-malignant pain, but create an environment that actually demands it. Instead of fighting a losing battle against the existing medical framework, create an entirely new one — one that promotes opioid and opiate painkillers for everyday aches and pains — and work from within it.

To understand just how the American medical system became corrupted in the 2000s, you have to understand the role of Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO), the most powerful accreditation institution in the world.

The Joint Commission is the gatekeeper. They’re the last line of defense between the patients over here and the drugs over there. The Joint Commission is a nonprofit organization based out of a Chicago suburb, charged with setting the standards of care for hospitals in this country and accrediting more than 20,000 facilities in all but four states. They’re the ones tasked with inspecting hospitals and ensuring adequate care is being given and standards are being met. They also issue directives in care.

In 2001, while the pharmaceutical lobby spent just under $100 million in lobbying efforts, the Joint Commission issued a new directive to its 20,000+ hospitals across the country:

It was time to start treating pain.

And who did the Joint Commission bring in to teach the hospitals how to treat the pain?

Purdue Pharma.

According to the United States General Accounting Office’s report to Congressional Request in December, 2003, the Joint Commission allowed Purdue Pharma to fund the “pain management educational courses” that taught the new standard of care for treating pain to JCAHO hospitals and facilities. And despite being cited twice by FDA for OxyContin advertisements in medical journals that violated the federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic (FD&C) Act, Purdue was allowed to disperse materials to educate doctors on pain management.

With access to America’s hospitals, Purdue then began funding more than 20,000 pain-related “educational programs” through financial grants and direct sponsorships. They used these grants to provide presentations and demonstrations to entire hospital staffs and present at state and local medical conferences, providing doctors with continuing medical education (CME) units.

The inmates weren’t running the asylum. The inmates had torn the asylum down, built a new one, and called it a hospital.

With pain management now mandated by the Joint Commission, Purdue began funding groups such as the American Chronic Pain Association (ACPA) and the American Pain Society (APS). These vocal groups began demanding doctors start taking pain management seriously, bringing their message everywhere from state legislatures to medical conferences.

Organizations funded by the pharmaceutical industry were created that rated doctors based on their willingness to treat pain and encouraged many family practitioners to begin prescribing outside of their normal scope of practice. The local family doctor suddenly felt pressure to prescribe powerful narcotics he or she might not have fully understood, or else risk a scathing review from a group like the American Pain Society that could irreparably harm his or her practice.

To ensure legal protection for prescribers, pharmaceutical companies began lobbying state legislatures who, with no medical background, began passing laws protecting doctors from malpractice claims for overprescribing.

With the Joint Commission and state legislatures having opened their doors, Purdue Pharma set its sights on the Federation of State Medical Boards (FSMB). According to an investigation by John Fauber of The Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, the FSMB accepted a $100,000 donation from Purdue for “printing and distribution” of pamphlets explaining safe use and prescribing of opioid medications.

Coincidentally, while it accepted $100,000 from Purdue, the FSMB began calling for doctors to be punished for not adequately treating pain.

The system was collapsed and the floodgates were opened. With the channels flowing so freely, Purdue began focusing on the last line of defense for the American public: the doctors.

If Americans were going to demand opioid painkillers, Purdue was going to be the one to supply it.

________________________________________

For the Sinaloa, bribing and coercing the governments of both Mexico and the United States was only part of the plan. The product still needed to get to their regional hubs for distribution. To facilitate this transaction, the Sinaloa established a system of transportation and hubs that is on par with anything run by Amazon or FedEx.

Using America’s interstate highway system, product was shipped from border towns to regional hubs such as Atlanta, Los Angeles, and Chicago, where it was then sold wholesale to cartel-approved capos.

Product was then moved throughout the country to smaller wholesalers and down the drug food chain until it eventually made its way to your typical street hustler. As far as Guzman was concerned, the risk of selling dope retail far outweighed the reward. It wasn’t worth it. Hand-to-hands were left to small time dealers who were essentially Sinaloa subcontractors, whether they realized it or not.

The cartel even gave out free samples in multiple cities across the US in a direct-to-consumer marketing strategy. Addicts would then request Guzman’s heroin which then put pressure on the dealers to pressure the wholesalers to buy from the Sinaloa cartel.

For Guzman and the Sinaloa, the key was getting the product to the wholesalers, who became the vital cog between the cartel and the American public.

Nowhere has the Sinaloa demonstrated the efficiency of its hub-wholesaler system more than it has in Chicago. In a fantastic piece written by Jason McGahan for Chicago Magazine, the Sinaloa is shown to have a near monopoly on narcotics in the city, controlling 70–80 percent of the drug trade.

The US Department of Justice identified Chicago as the number one destination for heroin entering the United States. Guzman refers to the city as his “home port.” According to then-US Attorney Patrick Fitzgerald, the Sinaloa sold more than $6 billion worth of narcotics in the city between 1990 and 2008. But perhaps our perspective is skewed. Perhaps instead we should ask why the people of Chicago felt the need to buy $6 billion worth of narcotics from the Sinaloa in that time period. While painful, that would at least force us to see drugs for what they are: a commodity, adhering strictly to the rule of supply and demand.

With statements like Fitzgerald’s, which focus on the supply side, it’s easy to lose sight of the fact that without a demand, the Sinaloa would not have a product to supply. The amount of effort required to take a plant from Colombia or Guerrera and get it into a syringe in Chicago is gargantuan. Without the demand, the supply would follow market principles and dry up.

But the demand in Chicago represents what has been happening throughout the rest of the country since 2000. Chicago is no anomaly. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, heroin overdoses in the US have quadrupled between 2000 and 2013, with the biggest jumps occurring between 2010 and 2013.

With heroin use more than doubled since 2000, Guzman’s profits were climbing, producing a single, glaring question:

What in the hell was fueling this demand?

________________________________________

For Purdue, successfully infiltrating the American medical system at every level — from the hospitals to the medical boards — was only part of the plan. All the literature it handed out and the hospital seminars it taught and continuing education units it granted physicians — these only opened the channels through which prescriptions could be written.

But could be written doesn’t turn a profit.

Sure, the drugs could be prescribed under new guidelines and directives. Mild pain, severe pain, chronic pain, acute pain, it didn’t matter. Purdue helped mold a system that was now conducive to throwing handfuls of narcotics at anything that was even the slightest bit uncomfortable. What it set out to do next was exploit the very holes in the system they themselves created and get OxyContin into the hands of an American public. Get the drugs over here to the people over there.

And taking a page out of their late brother Arthur’s playbook, Raymond and Mortimer Sackler set Purdue Pharma out on the most sophisticated and intricate pharmaceutical marketing campaign in history.

Scraping data from whichever pharmacies and medical boards were willing to sell it, along with records of doctors who’d prescribed Purdue painkillers in the past, Purdue compiled a list of the physicians across the country who wrote the most prescriptions for narcotic painkillers. No effort was made to distinguish between doctors who specialized in pain management and those who did not.

In fact, Purdue set its focus on primary care physicians. Family practitioners who typically:

• Saw the highest number of patients.

• Spend on average less than 10 minutes with each patient, encouraging a quick fix for treating pain.

• Had the least amount of education — if any — on treating chronic pain.

• Had little education on the risks of OxyContin outside of what they were taught by Purdue’s own sales staff.

Family practitioners were being squeezed from seemingly every direction. With groups like the American Pain Society publishing rankings of doctors based on their willingness to prescribe narcotics, and the Federation of State Medical Boards calling for doctors to be punished for not adequately treating pain, Purdue had successfully turned the local doctor’s office into a distribution hub for OxyContin.

Between 1996 and 2003, Purdue increased its sales force from 618 to 1,067. Targeting the physicians who (depending on who you talk to) either should have known better or never stood a chance, Purdue’s sales reps were unleashed, telling doctors across the country how safe OxyContin was to prescribe for non-cancer pain.

OxyContin, claimed Purdue’s sales force, had less than 1 percent chance of addiction.

OxyContin, they claimed, didn’t produce a high when taken.

OxyContin users, they assured doctors, were in no danger of building up a tolerance to the drug, a sure sign of physical addiction.

All lies, and Purdue knew they were lies. Each one resoundingly disproven, but far too late.

Many of these family practitioners were already spread thin. They relied on the information given to them by pharmaceutical reps who had a very strong financial incentive to mislead or flat-out lie to them. Each sales rep was given a quota for how many prescriptions of OxyContin their doctors had to prescribe, and a lucrative bonus structure was put in place. By 2001, the average salary for a Purdue Pharma sales representative was $55,000 with an average annual bonus of $71,500.

According to the GAO report to Congress, by 2003, primary care physicians — many of whom had no business treating chronic pain — were writing more than half of all OxyContin prescriptions. Pills were practically pouring into the streets. At the time, the DEA worried publicly that OxyContin was being prescribed overwhelmingly by doctors who were inadequately trained in pain management, but there was little the system could do. The system that should have stopped the problem had been compromised.

Purdue even gave out free samples, a curious gesture if you truly believe your product is non-addictive. Using a patient starter coupon, the first dosing was free. By 2001, about 34,000 coupons had been redeemed. By marketing directly to the consumer, Purdue knew that after the first taste — the free taste — many would come back to their doctors demanding another prescription for OxyContin, which is exactly what happened.

By 2000, several states, particularly in the Kentucky-West Virginia-Appalachia region, were reporting wide abuse of the drug. Addicts had learned how to peel the plastic coating off of the tablet and crush it up and snort, smoke, and inject it. Pharmacy robberies became common, with assailants bypassing the cash register and going straight for the bottles of OxyContin. Studies show that it was around 2001 when heroin in the US began its upward trajectory, as addicts who abused OxyContin — many of whom got hooked unintentionally after an injury — found heroin to be much cheaper for the same high.

To the addict, it didn’t matter. Heroin or Oxy. Coke or Pepsi. Different packaging, same taste. Both will quench your thirst.

In 1997, there were 670,000 prescriptions for OxyContin written in the US. By 2001–2002, that number increased to 14 million, bringing Purdue a profit of $3 billion. By 2001, OxyContin became the most widely prescribed narcotic painkiller in the US. The Sackler family business and its sophisticated marketing plan, torn directly from the pages of the Arthur Sackler manual on how to influence physicians, was a success.

addictionunscripted.com/kingpinsoxycontin-heroin-and-the-sackler-sinaloa-connection/