You may have heard that the internet is winning: net neutrality was saved, broadband was redefined to encourage higher speeds, and the dreaded Comcast-Time Warner Cable megamerger potentially thwarted. But the harsh reality is that America's internet is still fundamentally broken, and there's no easy fix.

FCC Passes Strongest Net Neutrality Rules In America's History

The open internet finally got the protection it deserves from profit-hungry cable companies. The… Read more

An Economy Built on Wires

When I say "fundamentally broken" I don't just mean that it's slow and shitty, though there is that. It's also broken as a paid service.

The internet is a tangible thing, a network of infrastructure pulsing with light, winding its way into and beneath buildings. It's also a marketplace. There is the physical location where the fiber-optic cables full of data cross, and then there are the financial deals that direct the traffic down each specific set of wires. This combination of physical wires and ephemeral business transactions will shape the future of the digital world.

In order to comprehend just how broken internet service is, you first have to understand how the physical infrastructure of the internet works. Former Gizmodo contributor Andrew Blum described the underlying infrastructure wonderfully his book about the physical heart of the internet, Tubes: A Journey to the Center of the Internet:

In the basest terms, the internet is made of pulses of light. Those pulses might seem miraculous, but they're not magic. They are produced by powerful lasers contained in steel boxes housed (predominantly) in unmarked buildings. The lasers exist. The boxes exist. The internet exists…

There's also wireless data of course, but even those signals need physical towers to send and receive them.

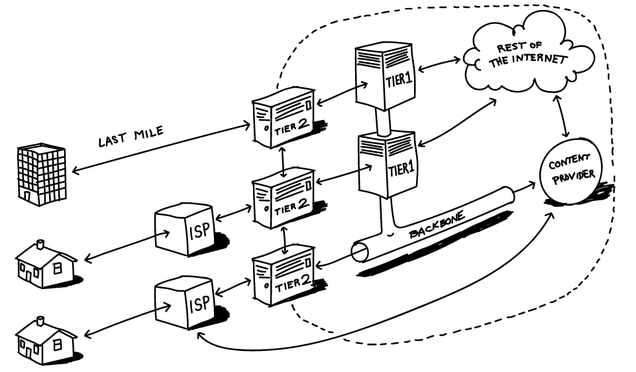

Those pulses of lights—which are packets of data—travel through the internet's wires, taking wrong turns, finding faster routes, and eventually reaching their destinations. But each of those routes is owned and maintained by somebody. If you think of the wires as roads, the setup is something like city streets, state highways, and interstates. In internet terms, those different kinds of roads are called tiers, and there are many network tiers stacked up across the US's continent-spanning network.

Tier 1 is the most powerful as it more or less makes up the backbone of the internet. These are the networks that span the entire globe, sending data under the ocean to far-flung places, the ones that never need to connect to another network to deliver a packet of content. There are only a handful of such networks, run by global corporations like AT&T and Verizon.

The smaller, tier 2 networks connect with each other and with the internet backbone to make it more efficient for those packets of data to reach their destinations. This is the level where a lot of corporate handshake deals to direct traffic take place. And then there's the so-called "last mile." You've probably heard a lot about this idea, and how traffic gets across it.

The last mile is the part of the data's voyage that takes it from local utility poles or underground tubes, into your house, and through the cable that plugs into your computer. It's literally the last stretch of infrastructure that data must traverse on its long journey from the server where it's hosted, to your web browser or email client or whatever. It's the physical infrastructure that connects individual homes to the rest of the network. This is the part of the internet that the new Federal Communications Commission's rules regulate.

The Decaying Last Mile

In the US, the last mile of internet infrastructure is an enormous problem. There are two reasons for this: technical restraints holding back the bandwidth needed to support modern-day internet traffic, and a lack of competition between the major carriers selling internet service to the end user.

Most of America's telecommunications infrastructure relies on outdated technology, and it runs over the same copper cables invented by Alexander Graham Bell over 100 years ago. This copper infrastructure—made up of "twisted pair" and coaxial cables—was originally designed to carry telephone and video services. The internet wasn't built to handle streaming video or audio.

When your streaming video reaches that troubled last mile of copper, those packets will slam on their brakes as they transition from fiber optic cables to copper coaxial cables. Copper can only carry so much bandwidth, far less than what the modern internet demands. Only fiber optic cables, thick twists of ultra-thin glass or plastic filaments that allow data to travel at the speed of light, can handle that bandwidth. They're also both easier to maintain and more secure than copper.

As consumers demand more bandwidth for things like streaming HD movies, carriers must augment their networks—upgrade hardware, lay more fiber, hire more engineers, etc.—to keep traffic moving freely between them. But that costs big money—like, billions of dollars in some cases. Imagine the cost of swapping out the coaxial cables in every American home with fiber optic cables. It's thousands of dollars per mile according to some government records.

And here's the kicker. The last mile infrastructure is controlled by an oligarchy—three big cable companies: Comcast, Time Warner Cable, and Verizon. You know this well. One in three Americans only have one choice for broadband service; most of the others only have two internet providers to choose from.

Without competition, there's no incentive for internet providers to improve improve infrastructure. These massive telecom companies create a bottleneck in the last mile of service by refusing to upgrade critical infrastructure. And they can charge exorbitant prices for the sub-par service while they're at it.

So your internet is shitty and slow and expensive.

The Network of Bureaucracy

If you want to load a webpage or watch a movie on Netflix, it's not just the last mile of infrastructure that slows down your internet, however. It's also the tier 2 networks, where the weird web of business connections starts tangling things up.

Like last mile infrastructure, there's only a small handful of companies controlling much of the backbone of the internet. Including, once again, telecom giants AT&T and Verizon. AT&T and Verizon not only control tier 1 network, they're also the big players on tier 2, which gives them a huge amount of bargaining power, and a huge amount of bureaucratic control over your slow and shitty internet.

The other carriers that operate tier 2 networks are companies you probably haven't heard of—Cogent and Zayo are a couple—and they're integral to the internet's success as a global network. These are the networks that manage the crossroads of the internet, making deals that dictate how traffic travels between networks.

A rough sketch of how the internet works. On the left, you have end users—homes and business. On the right, you have the networks making the deals that dictate how internet traffic flows around the globe. Note how content providers (Netflix, YouTube) peer directly with carriers.

Regardless of the physical infrastructure, data can only travel as fast as its predetermined route allows. If tier 2 networks don't strike the right agreements with other networks, that could mean that your data will take a longer route to its destination.

Broadly speaking, a tier 1 network can reach every part of the internet without paying for transit on another network; these are the internet's biggest power brokers. But each of the lesser-known tier 2 middleman carriers must depend on other networks to provide their customers with access to all of the content on the internet.

So picture a map of the internet. If every single network agreed to let other networks use its infrastructure data would flow freely between all points. Unfortunately, not all of the tier 2 networks cooperate.

This illustration shows the network of Level 3, a tier 1 carrier. The yellow lines are wholly owned and operated by Level 3, and the orange ones are shared with other carriers. In total, it's a sprawling 180,000 miles of fiber.

To keep traffic moving between networks, the carriers have to make interconnect agreements. One type is called a peering agreement, where two carriers exchange traffic freely for mutual benefit. The other is a transit agreement, exchanging traffic for a fee. The economics of these agreements are quite complex—here's a great explainer—but suffice it to say the larger the network, the fewer transit agreements it must pay for.

Tier 2 carriers also forge peering and transit agreements with content providers like Google, Amazon, and Netflix to provide more direct routes to consumers.

This gets complicated because you have a countless number of different networks relying on a limited amount of infrastructure. While fixing the decaying last mile means monopolistic telecom firms shelling out to upgrade copper wires, fiber optic cable is already the industry standard on tier 2 networks—so your internet speeds are affected more by how well these tier 2 carriers are getting along. When these deals go wrong, carriers end up in locked in negotiations that mean you'll wait longer for webpages to load.

The Fiber Future Relies on Competition

In a climate without sufficient competition, American carriers can refuse to improve infrastructure and augment capacity without the fear of losing customers. Where are they going to go? They can either pay a high price for bad service or pay nothing for no service. This has been the status quo in the USA for years, and companies like Verizon have worked hard to keep this status quo by preventing the FCC from doing its job.

That's also why carriers like Verizon are going straight to content providers like Netflix and asking it to pay for more direct routes to customers. Why would Verizon spend its own money on infrastructure, when it can get a content provider to pick up the tab?

This is where the net neutrality debate comes from. The FCC is finally getting aggressive about protecting the open web, and that's great. But net neutrality is not enough. Improving your slow and shitty internet comes down to increasing competition. We need to build new networks with better last mile technology that will give tier 2 networks an alternative to the big cable cartel.

This is going to require some radical approaches, like the bootstrapped ISPs and experimental municipal broadband networks we're starting to see.

While laying fiber is wildly expensive, startups could take a different tack. A San Francisco local ISP called Monkeybrains is using roof-mounted wireless connections and direct fiber access to data centers to offer high speed wireless internet. It costs about $250 to set up the equipment to join Monkeybrains' innovative network, but after that, you can get "insane speeds" for just $35 a month.

There's also the option of building a network from the ground up, like the city of Chattanooga, Tennessee did a few years ago. Starting this year, the federal government is funneling more money towards municipal broadband projects that treat the internet more like a public utility and offer high speeds at low prices. Now it's up to the communities to start up their municipal broadband projects.

President Obama has applauded this path forward, and the FCC is paving the way by tweaking regulations so that help municipal broadband overcome regulations that have traditionally favored big cable and discouraged competition. Some cracks in the oligarchy are starting to show.

At the end of the day, America's broken internet isn't going to fix itself. Monopolistic problems deserve capitalistic solutions. In this case, it's competition—pure and simple. The alternative isn't just frustrating. It's dysfunctional.

Illustrations by Jim Cooke

http://gizmodoDOTcom/why-americas-internet-is-so-shitty-and-slow-1686173744