Human Experiment: The Effects of Sta...

Human Experiment: The Effects of Sta...  mouseclick

15 y

60,788

RR

mouseclick

15 y

60,788

RR

THE EFFECTS OF STARVATION ON BEHAVIOR

One of the roast important advancements in the understanding of eating disorders is the recognition that severe and prolonged dietary restriction can lead to serious physical and psychological complications. Many of the symptoms once thought to be primary features of anorexia nervosa are actually symptoms of starvation.

Given what we know about the biology of weight regulation, what is the impact of weight suppression on the individual? This is particularly relevant for those with anorexia nervosa, but is also important for people with eating disorders who have lost significant amounts of body weight. Perhaps the most powerful illustration of the effects of restrictive dieting and weight loss on behavior is an experimental study conducted almost 50 years ago and published in 1950 by Ancel Keys and his colleagues at the University of Minnesota (Keys et al., 1950). The experiment involved carefully studying 36 young, healthy, psychologically normal men while restricting their caloric intake for 6 months. More than 100 men volunteered for the study as an alternative to military service; the 36 selected had the highest levels of physical and psychological health, as well as the most commitment to the objectives of the experiment.

During the first 3 months of the experiment, the volunteers ate normally while their behavior, personality, and eating patterns were studied in detail. During the next 6 months, the men were restricted to approximately half of their former food intake and lost, on average, approximately 25% of their former weight. Figure 8.5 shows the Minnesota volunteers at mealtime, and Figure 8.6 reveals the physical results of the weight loss. Although this was described as a study of’ “semistarvation,” it is important to keep in mind that cutting the men’s rations to half of their former intake is precisely the level of caloric deficit used to define “conservative” treatments for obesity (Stunkard, 1987). The 6 months of weight loss were followed by 3 months of rehabilitation, during which the men were gradually refed. A subgroup was followed for almost 9 months after the refeeding began. Most of the results were reported for only 32 men, since 4 men were withdrawn either during or at the end of the semistarvation phase. Although the individual responses to weight loss varied considerably, the men experienced dramatic physical, psychological, and social changes. In most cases, these changes persisted during the rehabilitation or renourishment phase.

What makes the “starvation study” (as it is commonly known) so important is that many of the experiences observed in the volunteers are the same as those experienced by patients with eating disorders. This section of this chapter is a summary of the changes observed in the Minnesota study. All quotations followed by page numbers in parentheses are from the original report by Keys et al. (1950) and are used by permission of the University of Minnesota Press.

(FIGURE 8.5. Minnesota volunteers at mealtime. Copyright 1950 by the University of Minnesota Press. Reprinted by permission)

(FIGURE 8.6. Minnesota volunteers after weight loss. Photo by Wallace Kirkland. Copyright 1950 by Life-Time-Warner.)

Attitudes and Behavior Related to Food and Eating

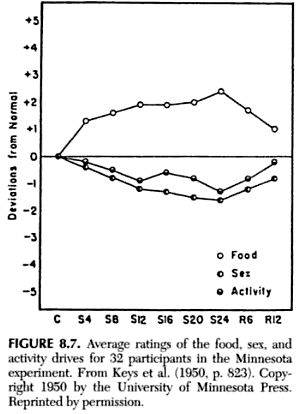

One of the most striking changes that occurred in the volunteers was a dramatic increase in food preoccupations. The men found concentration on their usual activities increasingly difficult, because they became plagued by incessant thoughts of food and eating. Figure 8.7 illustrates the increase in the average ratings of concern about food, as well as corresponding declines in interest in sex and activity, for 32 subjects at different stages of semistarvation and rehabilitation. Food became a principal topic of conversation, reading, and daydreams.

As starvation progressed, the number of men who toyed with their food increased. They made what under normal conditions would be weird and distasteful concoctions. (p. 832) . . . Those who ate in the common dining room smuggled out hits of food and consumed them on their bunks in a long-drawn-out ritual. (p. 833). Cookbooks, menus, and information bulletins on food production became intensely interesting to many of the men who previously had little or no interest in dietetics or agriculture. (p. 833) . . . [The volunteers] often reported that they got a vivid vicarious pleasure from watching other persons eating from just smelling food. (p. 834)

(FIGURE 8.7. Average ratings of the food, sex, and activity drives for 32 participants in the Minnesota experiment. From Keys et al. (1950, p. 823). Copyright 1950 by the University of Minnesota Press. Reprinted by permission)

In addition to cookbooks and collecting recipes, some of the men even began collecting coffeepots, hot plates, and other kitchen utensils. According to the original report, hoarding even extended to non-food-related items, such as: “old books, unnecessary second-hand clothes, knick knacks, and other ‘junk.’ Often after making such purchases, which could be afforded only with sacrifice, the men would he puzzled as to why they had bought such more or less useless articles” (p. 837). One man even began rummaging through garbage cans. This general tendency to hoard has been observed in starved anorexic patients (Crisp, Hsu, & Harding, 1980) and even in rats deprived of food (Fantino & Cabanac, 1980). Despite little interest in culinary matters prior to the experiment, almost 40% of the men mentioned cooking as part of their postexperiment plans. For some, the fascination was so great that they actually changed occupations after the experiment; three became chefs, and one went into agriculture!

During semistarvation, the volunteers eating habits underwent remarkable changes. The men spent much of the day planning how they would eat their allotment (If food. Much of their behavior served the purpose (If prolonging ingestion and increasing the appeal or salience of food. The men often ate in silence and devoted total attention to food consumption.

The Minnesota subjects were often caught between conflicting desires to gulp their food down ravenously and consume it slowly so that the taste and odor of each morsel would be fully appreciated. Toward the end of starvation some of the men would dawdle for almost two hours over a meal which previously they would have consumed in a matter of minutes.. . . They did much planning as to how they would handle their day’s allotment of food. (p. 833)The men demanded that their food be served hot, and they made unusual concoctions by mixing foods together, as noted above. There was also a marked increase in the use of salt and spices. The consumption of coffee and tea increased so dramatically that the men had to be limited to 9 cups per day; similarly, gum chewing became excessive and had to be limited after it was discovered that one man was chewing as many as 40 packages of gum a day and “developed a sore mouth from such continuous exercise” (p. 835).

During the 12-week refeeding phase of the experiment, most of the abnormal attitudes and behaviors in regard to food persisted. A small number of men found that their difficulties in this area were quite severe during the first 6 weeks of refeeding:

In many cases the men were not content to eat ‘normal” menus but persevered in their habits of making fantastic concoctions and combinations. The free choice of ingredients, moreover, stimulated “creative” and “experimental” playing with food . . . licking of plates and neglect of table manners persisted. (p. 843)

Binge Eating

During the restrictive dieting phase of the experiment, all of the volunteers reported increased hunger. Some appeared able to tolerate the experience fairly well, but for others it created intense concern and led to a complete breakdown in control. Several men were unable to adhere to their diets and reported episodes of binge eating followed by self-reproach. During the eighth week of starvation, one volunteer “flagrantly broke the dietary rules, eating several sundaes and malted milks; he even stole some penny candies. He promptly confessed the whole episode, [and] became self-deprecatory (p. 884). While working in a grocery store, another man suffered a complete loss of will power and ate several cookies, a sack of popcorn, and two overripe bananas before he could “regain control of himself. He immediately suffered a severe emotional upset, with nausea, and upon returning to the laboratory he vomited. ... He was self-deprecatory, expressing disgust and self-criticism. (p. 887)

One man was released from the experiment at the end of the semistarvation period because of suspicions that he was unable to adhere to the diet. He experienced serious difficulties when confronted with unlimited access to food: “He repeatedly went through the cycle of eating tremendous quantities of food, becoming sick, and then starting all over again” (p. 890).

During the refeeding phase of the experiment, many of the men lost control of their appetites and “ate more or less continuously” (p. 843). Even after 12 weeks of refeeding, the men frequently complained of increased hunger immediately following a large meal:

[One of the volunteers] ate immense meals (a daily estimate of 5,000—6,000 cal.) and yet started “snacking” an hour after he finished a meal. [Another] ate as much as he could hold during the three regular meals and ate snacks in the morning, afternoon and evening. (p. 846)

Such overeating took its toll:

This gluttony resulted in a high incidence of headaches, gastrointestinal distress and unusual sleepiness. Several men had spells of nausea and vomiting. One man required aspiration and hospitalization for several (lays. (p. 843)

During the weekends in particular, some of the men found it difficult to stop eating. Their daily intake commonly ranged between 8,000 and 10,000 calories, and their eating patterns were described as follows:

Subject No. 20 stuffs himself until he is bursting at the seams, to the point of being nearly sick and still feels hungry; No. 120 reported that he had to discipline himself to keep from eating so much as to become ill; No. I ate until he was uncomfortably full; arid subject No. 30 had so little control over the mechanics of “piling it in” that he simply had to stay away from food because he could not find a point of satiation even when he was “full to the gills.” I ate practically all weekend,” reported subject No. 26.... Subject No. 26 would just as soon have eaten six meals instead of three. (p. 847)

After about 5 months of refeeding, the majority of the men reported some normalization of their eating patterns, but for some the extreme overconsumption persisted: “No. 108 would eat and eat until he could hardly swallow any more and then he felt like eating half an hour later” (p. 847). More than 8 months after renourishment began, most men had returned to normal eating patterns; however, a few were still eating abnormal amounts: “No. 9 ate about 25 percent more than his pre-starvation amount; once he started to reduce but got so hungry he could not stand it” (p. 847). Factors distinguishing men who rapidly normalized their eating from those who continued to eat prodigious amounts were not identified. Nevertheless, the main findings here are as follows: Serious binge eating developed in a subgroup of men, and this tendency persisted in some cases for months after free access to food was reintroduced; however, the majority of men reported gradually returning to eating normal amounts of food after about 5 months of refeeding. Thus, the fact that binge eating was experimentally produced in some of these normal young men should temper speculations about primary psychological disturbances as the cause of hinge eating in patients with eating disorders. These findings are supported by a large body of research indicating that habitual dieters display marked overcompensation in eating behavior that is similar to the binge eating observed in eating disorders (Polivy & Herman, 1985, 1987; Wardle & Beinart, 1981).

Emotional and Personality Changes

The experimental procedures involved selecting volunteers who were the most physically and psychologically robust: “The psychobiological ‘stamina’ of the subjects was unquestionably superior to that likely to be found in any random or more generally representative sample of the population” (pp. 915-916). Although the subjects were psychologically healthy prior to the experiment, most experienced significant emotional deterioration as a result of semistarvation. Most of the subjects experienced periods during which their emotional distress was quite severe; almost 20% experienced extreme emotional deterioration that markedly interfered with their functioning.

Depression became more severe during the course of the experiment. Elation was observed occasionally, but this was inevitably followed by “low periods.” Mood swings were extreme for some of the volunteers:

[One subject] experienced a number of periods in which his spirits were definitely high These elated periods alternated with times in which he suffered “a deep dark depression. [He] felt that he had reached the end of his rope [and] expression the fear that he was going crazy.. . [and] losing his inhibitions. (p. 903)

Irritability and frequent outbursts of anger were common, although the men had quite tolerant dispositions prior to starvation. For most subjects, anxiety became more evident. As the experiment progressed, many of the formerly even-tempered men began biting their nails or smoking because they felt nervous. Apathy also became common, and some men who had been quite fastidious neglected various aspects of personal hygiene.

During semistarvation, two subjects developed disturbances of “psychotic” proportions. One of these was unable to adhere to the diet and developed alarming symptoms:

[He exhibited] a compulsive attraction to refuse amid a strong, almost compelling, desire to root in garbage cans [for food to eat]. He became emotionally disturbed enough to seek admission voluntarily to the psychiatric ward of the University Hospitals. (p. 890)

After 9 weeks of starvation, another subject also exhibited serious signs of disturbance:

[He went on a] spree of shoplifting, stealing trinkets that had little or no intrinsic value. . . . He developed a violent emotional outburst with flight of ideas, weeping, talk of suicide and threats of violence. Because of the alarming nature of his symptoms, he was released from the experiment and admitted to the psychiatric ward of the University Hospitals. (p. 885)

During the refeeding period, emotional disturbance (lid not vanish immediately hut persisted for several weeks, with some men actually becoming more depressed, irritable, argumentative, and negativistic than they had been during semistarvation. After two weeks of refeeding, one man reported his extreme reaction in his diary:

I have been more depressed than ever in my life…. I thought that there was only one thing that would pull me out of the doldrums, that is release from C.P.S. [the experiment] I decided to get rid of some fingers. Ten days ago, I jacked up my car and let the car fall on these fingers…. It was premeditated. (pp. 894-895)

Several days later, this man actually did chop off three fingers of one hand in response to the stress.

Standardized personality testing with the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI) revealed that semistarvation resulted in significant increases on the Depression, Hysteria, and Hypochondriasis scales. This profile has been referred to as the neurotic triad” and is observed among different groups of disturbed individuals (Greene, 1980). The MMPJ profiles for a small minority of subjects confirmed the clinical impression of incredible deterioration as a result of semistarvation. Figure 8.8 illustrates one man’s personality profile: Initially it was well within normal limits, but after 10 weeks of semistarvation and a weight loss of only about 4.5 kg (10 pounds, or approximately 7% of his original body weight), gross personality disturbances were evident. On the second testing, all of the MMPI scales were elevated, indicating severe personality disturbance on scales reflecting neurotic as well as psychotic traits. Depression and general disorganization were particularly striking consequences of starvation for several of the men who became the most emotionally disturbed.

Social and Sexual Changes

The extraordinary impact of scm istarvation was reflected in the social changes experienced by most of the volunteers. Although originally quite gregarious, the men became progressively more withdrawn and isolated. Humor and the sense of comradeship diminished amidst growing feelings of social inadequacy:

Social initiative especially and sociability in general, underwent a remarkable change. The men became reluctant to plan activities, to make decisions, and to participate in group activities.... They spent more and more time alone. It became too much trouble” or “too tiling” to have contact with other people. (pp. 836-837)

The volunteers’ social contacts with women also declined sharply during semistarvation. Those who continued to see women socially found that the relationships became strained. These changes are illustrated in the account from one man’s diary:

I am one of about three or four who still go out with girls. I fell in love with a girl during the control period but I see her only occasionally noxv. It’s almost too much trouble to see her even when she visits me in the lab. It requires effort to hold her hand. Entertainment must be tame. If we see a show, the most interesting part of it is contained in scenes where people are eating. (p. 853)

(FIGURE 8.8. Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI) scores for one participant in the Minnesota experiment during the control period (C), and after 10 weeks of calorie restriction (S10) and weight loss of about 7% of his control weight. T scores between 30 and 70 are in the normal range. Hs, Hypochondriasis; D, Depression; Hy, Hysteria; Pd, Psychopathic Deviate; Mf, Masculinity-Femininity; Pa, Paranoia; Pt, Psychasthenia; Sc, Schizophrenia; Ma, Hypomania. From Keys et al. (1950, p. 856). Copyright 1950 by the University of Minnesota Press. Reprinted by permission)

Sexual interests were likewise drastically reduced (see Figure 8.7). Masturbation, sexual fantasies, and sexual impulses either ceased or became much less common. One subject graphically stated that he had “no more sexual feeling than a sick oyster.” (Even this peculiar metaphor made reference to food.) Keys et al. observed that “many of the men welcomed the freedom from sexual tensions and frustrations normally present in young adult men” (p. 840). The fact that starvation perceptibly altered sexual urges and associated conflicts is of particular interest, since it has been hypothesized that this process is the driving force behind the dieting of many anorexia nervosa patients. According to Crisp (1980), anorexia nervosa is an adaptive disorder in the sense that it curtails sexual concerns for which the adolescent feels unprepared.

During rehabilitation, sexual interest was slow to return. Even after 3 months, the men judged themselves to be far from normal in this area. However, after 8 months of re-nourishment, virtually all of the men had recovered their interest in sex.

Cognitive Changes

The volunteers reported impaired concentration, alertness, comprehension, and judgment during semistarvation; however, formal intellectual testing revealed no signs of diminished intellectual abilities.

Physical Changes

As the 6 months of semistarvation progressed, the volunteers exhibited man)’ physical changes, including gastrointestinal discomfort; decreased need for sleep; dizziness; headaches; hypersensitivity to noise and light; reduced strength; poor motor control; edema (an excess of fluid causing swelling); hair loss; decreased tolerance for cold temperatures (cold hands and feet); visual disturbances (i.e., inability to focus, eye aches, “spots” in the visual fields); auditory disturbances (i.e., ringing noise in the ears); and paresthesias (i.e., abnormal tingling or prickling sensations, especially in the hands or feet).

Various changes reflected an overall slowing of the body’s physiological processes. There were decreases in body temperature, heart rate, and respiration, as well as in basal metabolic rate (BMR). BMR is the amount of energy (in calories) that the body requires at rest (i.e., no physical activity) in order to carry out normal physiological processes. It accounts for about two-thirds of the body’s total energy needs, with the remainder being used during physical activity. At the end of semistarvation, the men’s BMRs had dropped by about 40% from normal levels. This drop, as well as other physical changes, reflects the body’s extraordinary ability to adapt to low caloric intake by reducing its need for energy. As one volunteer described it, he felt as if his “body flame [were] burning as low as possible to conserve precious fuel and still maintain life process” (p. 852). Recent research has shown that metabolic rate is markedly reduced even among dieters who do not have a history of dramatic weight loss (Platte, Wurrnser, Wade, Mecheril, & Pirke, 1996). During refeeding, Keys et al. found that metabolism speeded up, with those consuming the greatest number of calories experiencing the largest rise in BMR. The group of volunteers who received a relatively small increment in calories during refeeding (400 calories more than during semistarvation) had no rise in BMR for the first 3 weeks. Consuming larger amounts of food caused a sharp increase in the energy burned through metabolic processes.

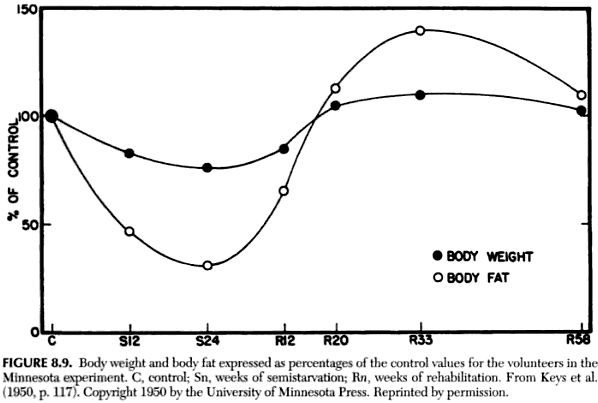

The changes in body fat and muscle in relation to overall body weight during semistarvation and refeeding are of considerable interest (Figure 8.9). While weight declined about 25%, the percentage of body hit fell almost 70%, and muscle decreased about 40%. Upon refeeding, a greater proportion of the “new weight” was fat; in tile eighth month of rehabilitation, the volunteers were at about 110% of their original body weight hut had approximately 140% of their original body fat!

How did the men feel about their weight gain during rehabilitation? “Those subjects who gained the most weight became concerned about their increased sluggishness, general flabbiness, and the tendency of fat to accumulate in the abdomen and buttocks” (p. 828). These complaints are similar to those of many eating disorder patients as they gain weight. Besides their typical fear of’ weight gain, they often report “feeling fat” and are worried about acquiring distended stomachs. However, as indicated in Figure 8.9, the body weight and relative body fat of the Minnesota volunteers was at the preexperiment levels after about 9 months of rehabilitation

(FIGURE 8.9. Body weight and body fat expressed as percentages of the control values for the volunteers in the Minnesota experiment. C, control; Sn, weeks of semistarvation; Rn, weeks of rehabilitation. From Keys et al. (1950, p. 117). Copyright 1950 by the University of Minnesota Press. Reprinted by permission)

Physical Activity

In general, the men responded to semistarvation with reduced physical activity. They became tired, weak, listless, and apathetic, and complained of lack of energy. Voluntary movements became noticeably slower. However, according to Keyes et al., “some men exercised deliberately at times. Some of them attempted to lose weight by driving themselves through periods of excessive expenditure of energy in order either to obtain increased bread rations ... or to avoid reduction in rations” (p. 828). This is similar to the practice of some eating disorder patients, who feel that if they exercise strenuously, they can allow themselves a bit more to eat. The difference is that for those with eating disorders, the caloric limitations are self-imposed.

Significance of the “Starvation Study”

As is readily apparent from the preceding description of the Minnesota experiment, many of the symptoms that might have been thought to he specific to anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa are actually the results of starvation (Pirke & Ploog, 1987). These are not limited to food and weight, but extend to virtually all areas of psychological and social functioning. Since many of the symptoms that have been postulated to cause these disorders may actually result from undernutrition, it is absolutely essential that weight be returned to “normal” levels so that psychological functioning can be accurately assessed.

The profound effects of starvation also illustrate the tremendous adaptive capacity of the human body and the intense biological pressure on the organism to maintain a relatively consistent body weight. This makes complete evolutionary sense. Over hundreds of thousands of years of human evolution, a major threat to the survival of the organism was starvation. If weight had riot been carefully modulated and controlled internally, early humans most certainly would simply have died when food was scarce or when their interest was captured by countless other aspects of living. The Keys et al. “starvation study” illustrates how the human being becomes more oriented toward food when starved and how other pursuits important to the survival of the species (e.g., social and sexual functioning) become subordinate to the primary drive toward food.

One of the most notable implications of the Minnesota experiment is that it challenges the popular notion that body weight is easily altered if one simply exercises a bit of “willpower.” It also demonstrates that the body is not simply “reprogrammed” at a lower set point once weight loss has been achieved. The volunteers’ experimental diet was unsuccessful in overriding their bodies’ strong propensity to defend a particular weight level. Again, it is important to emphasize that following the months of refeeding, the Minnesota volunteers did not skyrocket into obesity. On the average, they gained hack their original weight plus about 10%; then, over the next 6 months, their weight gradually declined. By the end of the follow-up period, they were approaching their preexperiment weight levels.

Sources: Handbook of Treatments for Eating Disorders - page 153 - 161 (Free on Google Books)

For information. Please note:

- the experiment was unethical as it was offered to young fit men as an alternative to serving in the armed forces, and such an experiment is unlikely to be done again on humans

- They year is 1950, therefore average body mass index would have been much lower then today, as would the food have been different

More

- Re: Human Experiment: The Effects of... meganrose

15 y

49,321

This is a reply to # 1,430,817Wow, that is crazy.

But isn't this different than fasting?? Because they were in starvation mode but our bodies are in ketosis?- Re: Human Experiment: The Effects of... ActionGirl

15 y

49,513

MoreThis is a reply to # 1,430,852I do not see the difference between fasting verses calorie restriction. Your body in ketosis has nothing to do with your behavior and daily rituals. I think a lot of peoples in this community will vouch that their daily habits and leisure time is altered during fasts.

- Re: Human Experiment: The Effects of... mouseclick

15 y

49,414

This is a reply to # 1,430,852Yes it is different I think. But the reason I posted it is because a lot of people here are not purely fasting, for example some may be taking supplements some may be doing alternate day fasting and so on (as indeed I considered). I deliberately didn't comment because I haven't had time to digest it all (pardon the pun), but what I did notice is that a lot of the symptoms those guys had are similar to what we see here sometimes.

Where you draw the line between fasting and starving, others can comment on, but I think it's useful to have as reference material just as a check to see anyone who is not fasting properly may recognize any of the symptoms themselves.

Remember also that experiment was in 1950, it is likely that many people nowadays eat processed food between fasts, with far lower nutrient content per calorie than what those guys were on. So people eat food without enough nutrients and get fat, then fast (zero nutrients) then eat low nutrient food again. And a lot of people that fast to lose weight may want to be eat lightly between fasts, thus exacerbating the problem.

The metabolic set point issue may also be interesting to fasting people who get stuck at a plateau when trying to lose weight.

And of course it's probably a unique study that will never be repeated. It wasn't very ethical offering it as an alternate to national service, I don't think we would do that these days. Well, hopefully not. - Re: Human Experiment: The Effects of... Mighty.Sun.Tzu

15 y

49,710

R

This is a reply to # 1,430,852

"But isn't this different than fasting?? Because they were in starvation mode but our bodies are in ketosis?"

This is definately different from fasting. In fasting we are A) doing it because we want to and generally with some knowledge that keeps us from behaving hysterically... because we are not starving and we know we are not... and B) burning predominately fat for fuel in ketosis, i would say at a ratio of about 10:1 fat to protein in an amazingly protein sparing phenomenon. And even with the protein that is utilized, the most diseased or dead or otherwise worthless tissue is autolyzed preferentially.

In fasting, only upon the return of genuine hunger would we then be starving and only if we foolishly continued not to eat in the face of the most powerful feeling of natural hunger imaginable. In this experiment, these guys ran out of body fat to burn and then began to agressively feed on their own muscle. This can definatly be avoided in fasting.

""Carrington has well summed up the matter in these words: "Fasting is a scientific method of ridding the system of diseased tissue, and morbid matter, and is invariably accompanied by beneficial results. Starving is the deprivation of the tissues from nutriment which they require, and is invariably accompanied by disastrous consequences. The whole secret is this: fasting commences with the omission of the first meal and ends with the return of natural hunger, while starvation only begins with the return of natural hunger and terminates in death. Where the one ends the other begins. Whereas the latter process wastes the healthy tissues, emaciates the body, and depletes the vitality; the former process merely expels corrupt matter and useless fatty tissue, thereby elevating the energy, and eventually restoring the organism that just balance we term health.""" from Shelton: http://www.soilandhealth.org/02/0201hyglibcat/020127shelton.III/020127.ch6.htm

It is true that a faster can become preoccupied with food, most especially in beginners of the art, but i believe that this happens only infrequently in experienced fasters. With myself as an example, i am 10.4 days in and i have had only one serious food craving. I sniffed some food for about a half hour to ease myslef through it and the craving was gone. I most certainly do not spend my days fantasizing about food, though naturally i will occasionally think about it as yes, humans do enjoy food and it's pretty normal and healthy to miss it after many days without. If i knew nothing about fasting and had nothing but water for 10 days, i imagine i would be exhibiting a lot of the same hysterical behavior of these men who were quite literally starving at some point, even though i am not. But instead, i am as calm as a buddhist monk.

- Re: Let's not be misled by words mouseclick

15 y

49,326

End Constipation Now

Let oxygen remove old, impacted fecal matter as it detoxifies and...

Mercury Detox

Dental work and fillings, not a problem.

This is a reply to # 1,431,020I agree with you that a continuous fast is not the same as this.

It is unfortunate that this report is commonly called the "starvation study" or semi starvation study.

From what I have read so far it should be called the low calorie diet study.

Such a title would be quite unpalatable to some people connected with that industry I am sure. - Re: Human Experiment: The Effects of... ActionGirl

15 y

49,607

This is a reply to # 1,431,020I most certainly do not spend my days fantasizing about food, though naturally i will occasionally think about it as yes, humans do enjoy food and it's pretty normal and healthy to miss it after many days without.

From what I took from the report obsessing could possibly be with items besides food. One could start hording just about anything. It struck a cord since my longest fast (six years ago) I was hording all sorts of items like bath products, clothes and distilled water. My habits only changed months after the fast was completed. And I was not a beginner six years ago.- Re: Human Experiment: The Effects of... Mighty.Sun.Tzu

15 y

49,552

This is a reply to # 1,431,103

It's an interesting study to be sure. It's hard in such an experiment to isolate the variable you are attempting to research, in this case what they refer to as "semi-starvation". I kept thinking how these guys were basically prisoners, unable to return to their homes or to their normal lives... and how much of the symptoms they exhibited related to this rather than to the inadequate portions of food. Nothing specifically is mentioned about the control group and exactly how it was employed. A well controlled study would have had an equal number of subjects living in similar "prison like" conditions but with full rations of food to compare the differences in behavior between the two groups. Perhaps this is what the researchers did, but by the article, we don't know. The article neither goes into what the control group consisted of nor what kind of behaviors these subjects were exhibiting.

Hording non-food items didn't seem to be common in this study, seems just one individual was mentioned. Who knows what was going on with him and why he did it, but he seemed to be vastly in the minority.

What would also have been interesting would have been to have a 3rd group, semi-starved but educated on how best to emerge from this test, the importance of not eating too much too soon and the reasons behind it, much the way we in this forum are educated to do. It would be very easy to binge post-fast and to over-eat, just as it was for the "prisoners" from their "semi-starvation diet", but one big factor which separates those that do and those that don't is their level of knowledge in the area of how to properly break a fast (or in this case "semi-starvation diet") and how to continue to eat properly thereafter.

- Re: Human Experiment: The Effects of... chirontherainbowbridge

15 y

49,191

This is a reply to # 1,431,129"I kept thinking how these guys were basically prisoners, unable to return to their homes or to their normal lives... and how much of the symptoms they exhibited related to this rather than to the inadequate portions of food?"

yup. Serious deprivation: and don't forget they were "offered" this study in lieu of military duty. Enough food = love, or at least a certain sense of well-being, or autonomy, in unpleasant surroundings, in this respect.

(and actually I think the "hoarding" of teapots and such sounds like a sort of elegant twist on wanting to *give* love (or nurture) rather than just keep it for oneself. this also explains the way some of these fellows grew a new interest in feeding others (chefdom)

God bless them --it sounds gruelling, and wholly lacking in human warmth.- Edited #111629

15 y

48,995

This is a reply to # 1,431,139

LOL, I just noticed after my post, I read Chiron's, and she had already commented on the same thing!

- Edited #111629

15 y

48,995

- Edited #111629

15 y

49,117

This is a reply to # 1,431,129

"I kept thinking how these guys were basically prisoners, unable to return to their homes or to their normal lives... and how much of the symptoms they exhibited related to this rather than to the inadequate portions of food."

Sun,

They certainly were prisoners. The larger issue of the experiment was not even addressed in the article though, that is, they could either participate in the experiment, or be drafted. The starvation experiment was definitely unethical. But the problem remains that these men were facing a military draft if they did not take part. They really had no choice. I don't see how being put into that kind of a situation could not have had at least "some" effect on the behavior of the men in the starvation experiment.

- Re: Human Experiment: The Effects of... mouseclick

15 y

49,300

This is a reply to # 1,431,536Well then I agree with your deleted comments, lol!

No one with any moral sense would ever do an experiment like this on humans or animals.

However now that it's done, the results are invaluable.

What annoys me is that I can't get a copy of the original. After all those men suffered, they should put it online it if only as a tribute. The only place I found it was at a library in Mexico. As that review I quoted earlier said, it will be of great benefit to others.

- Re: Human Experiment: The Effects of... mouseclick

15 y

49,300

- Re: Human Experiment: The Effects of... chirontherainbowbridge

15 y

49,191

- Re: Human Experiment: The Effects of... Mighty.Sun.Tzu

15 y

49,552

- Re: Let's not be misled by words mouseclick

15 y

49,326

- Re: Human Experiment: The Effects of... ActionGirl

15 y

49,513

- Thank you ActionGirl

15 y

49,186

- Re: U R Welcome mouseclick

15 y

49,363

This is a reply to # 1,430,860I was against the morality of the test but I think it must be unique.

It is a stark contrast to calorie restriction, which improves physical health and longevity (though I had not thought about the emotional side before).

My guess is that it's all about getting enough nutrients, but I just don't know.- Re: U R Welcome ActionGirl

15 y

49,211

This is a reply to # 1,430,881The health and longevity went right over myhead. What interest me was the behavior of the individuals during restriction. I had notice a lot of the same traits in others and myself when fasting or dieting.

- Re: Emotional Effects of Dieting mouseclick

15 y

49,599

This is a reply to # 1,430,908

What's on my mind is why is this report hidden away, and I am wondering if this is anything to do with the slimming industry which is worth $40 billion in the USA and £2 billion in the UK. Surely this report is implying that EDs are caused by bad diet, and nothing to do with so called "mental ilness"?

Ancel Keys studied nutrition and went on to live till 100, but I don't think he knew what the vegsource docs know. And yeah, I guess younger people don't think about longevity, must remember that sometime, lol.

I have to go out soon but I'll have a dig around on this. Anyway, just quiclky I found this word document which may interest you and others. It seems to expand on what my OP was about. I have just pasted the emotional bit below, you'll have to click on the document to read the full text.

I guess if you think this is the problem, you can experiment with yourself as it were. Good luck if you do :)

The Emotional Effects of Dieting

The psychological as well as physiological effects of drastically reducing food intake have been well documented by Ancel Keys in a series of much quoted experiments conducted on young healthy male conscientious objectors without a history of weight problems . They participated in these experiments as an alternative to military duties during the Korean war. The men ate normally during the first three months of the experiment while their eating patterns and personalities were studied. They were then put on strict diets where their normal food intake was halved for a period of three months. Afterward they went through a three month rehabilitation period where they were reintroduced to eating normal amounts of food.

What happened suggests that the effects of dieting are far reaching. Food became the main topic of conversation reading and daydreams for almost all of the men. Men who previously had no particular interest in food and cooking became fascinated by cookery and menus. About half way through the semi starvation period 13 of the men expressed an interest in taking up cooking as a career after the experiment was over. Many of the men found it impossible to stick to the diet - they ate secretly on impulse and felt guilty afterwards. Psychologically they became more anxious and prone to feeling depressed , they had difficulty concentrating and they began to withdraw from other people and became less sociable. Two of the men had emotional breakdowns and one cut off the end of his finger apparently hoping that he would be excused from the study. The remained developed a “buddy” system to help them stop cheating.

The terrible internal conflicts which are the result of food restraint are a source of continual stress, according to psychologist Jane Warble. All dieters score higher than non dieters on measures of emotional agitation and are more likely to show impaired mental performance.

Dieting also changes the way we feel about our body. In the Keys experiment it was noted that men who had no previous concerns with their appearance and weight began to experience changes in the way they perceived their bodies, paradoxically several of the men complained about feeling overweight even though they had lost weight and they began to experience critical evaluations of their body shape and size.

At the end of the dieting period the men’s personalities reverted to normal . However many of them continued to have problems with eating. Even though they were allowed to eat as they wanted many of them found that they could not stop eating when they were full and generally ate more than they thought they wanted or was good for them. They continued to be preoccupied with food and some reported that their cravings were even worse than before. Many had cravings for specific foods such as sweets dairy products and nuts. Many of them snacked between meals even if they had not done so before. Another four weeks later ten of the 15 men who were still in touch with the researchers became so anxious about their weight that they put themselves on another diet and a few were continuing to eat prodigious quantities. Three moths after the experiment food was still a major concern for 15 out of the 24 men and this continued for a further 8 months after the diet was over.

Psychologists called Herman and Polivy at the University of Toronto have underlined the effect of food restriction on willpower in an experiment on dieting and non dieting students who were invited to eat as much ice cream as they liked after being given three different “pre loads” - one glass of milk shake, two milk shakes or nothing at all.

While the non-dieters behaved as expected, eating less ice cream after one milk shake than none, and even less ice cream after two, the dieters actually ate most ice cream after the biggest “pre load”.

According to the psychologist the effect of the milk shake was to undermine the dieters resolve, temporarily releasing them from their vows of abstinence. After the milk shake , instead of doing penance for the calorific sin, the dieter persists in sinful indulgence, say the psychologists. After all, if staying on the diet is no longer possible then why not make the most of the situation. This seductive thought process - I may as well be hanged for a sheep as a lamb - is a trap which awaits all dieters. After succumbing to one biscuit you feel such a failure you consume the whole packet. You decide to ditch the diet for the day and start again tomorrow.

But as Herman and Polivy point out, in anticipation of deprivation to come, dieters indulgences “ the night before” can reach legendary proportions. The seeming inability of diets to stop once they have started stem from the Faustian bargain they made with themselves at the start. Included in the loss of normal internal controls are the normal processes involving satiety. Dieters do not eat interminably once their rules are broken but they eat far more than non dieters do.

By denying themselves food, dieters also make it much more important. Dieters are more likely than nondieters to turn to food when they are emotionally anxious or depressed. This phenomenon is created by dieting itself. At a recent study carried out in London, female volunteers were divided into three groups, the first went on a strict diet, the second a rigorous exercise programme and the third neither dieted nor exercised.

After 5 weeks the subjects took part in an experiment which assessed their food intake while watching a stressful film. Bowls of sweets and nuts were left beside them and they were told to eat as they liked. Women in the diet group ate far more than the others.

So it seems the effects of reducing food intake for a period of time are powerful.. and what makes these experiments interesting is that the first described the experience of men who are not unduly concerned about food and weight. They experienced feelings and thoughts which are not unlike those experienced by people with anorexia - with their concerns about hoarding food and seeing themselves to be fatter than they were. What is more, the experience of dieting in itself - irrespective of personality and background engendered in the men in the Keys experiment, a concern about food and weight which they had not experienced previously. It is not unfair to assume that dieting will create these effects in all who try it out.

Aside from the psychological and physiological effects of dieting, when we consider advising people to diet we must bear in mind what we know about they way human beings respond to and comply with any kind of advice, medical and otherwise. Compliance will always be affected by the process itself whether it is simple or complex, the degree of behavioural change needed and whether it fits with the personality and lifestyle of the person. Compliance will be affected by the value of the outcome, and the goals of dieting - weight loss - may contain unrecognised difficulties if achieved. Compliance is also affected by many factors in the dieter herself, including beliefs about his or her personal efficacy, ability to handle lapses, singularity of purpose and ability to muster the right kind of social support. Kelly Brownell has also identified a crucial element influencing the prognosis of dieting behave which he defines as “emotional readiness.” This concept proposes that in order for dieting to be successful one has to go into “training” for the it in much the same way as one would go into training for other projects like climbing a mountain or studying for an exam.

- Re: Emotional Effects of Dieting chirontherainbowbridge

15 y

49,164

This is a reply to # 1,431,022i think what the wise person can get from this is that dieting is fundamentally flawed. It's been well documented (or simply seen) that it only leads to binging and more dieting...

The experience of being depirved (or depriving one's own self! which is what "dieting" is)is essentially an act of hate. And as such, the penance for that lack of love can

only be to suffer through excess. that's the convoluted way the mind might work when it's deprived of some essential nutrition, and sound thinking.

we have to consider the huge effects of the way 'dieters' are so often people who are starving in the real sense, no matter whether they are losing weight or gaining it.

They are mostly starved of real food. These experiemnts with ice cream, and candy and nuts and so on, seem to me to be more than a little misguided: those in charge reminding me of the kind of minds that experminet on animals and see nothing wrong in that.

Fasting, by contrast CAN be something quite different, (if it's approached not as penance: it's all about where the mind really locates itself, after all the stuff of personality is stripped away))OR it can be yet another form of deprivation, a lack of love leading to more lack of love.... thst sort of auroborus.

- Re: Emotional Effects of Dieting chirontherainbowbridge

15 y

49,164

- Re: Emotional Effects of Dieting mouseclick

15 y

49,599

- Re: U R Welcome ActionGirl

15 y

49,211

- Re: U R Welcome mouseclick

15 y

49,363

- Re: A little more information from W... mouseclick

15 y

49,549

This is a reply to # 1,430,817

I found this on Wikipedia. Click here for the full article, here is the "results" and "related work" sections near the end. This Ancel Keys is probably an interesting guy to check out.

Results

The full report of results from the Minnesota Starvation Experiment was published in 1950 in a two-volume, 1,385 page text entitled The Biology of Human Starvation (University of Minneapolis Press). The fifty chapters of this treatise contain an extensive analysis of the physiological and psychological data collected during the study together with a comprehensive literature review.

Among the many conclusions from the study was the confirmation that prolonged semi-starvation produces significant increases in depression, hysteria and hypochondriasis as measured using the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI), a standardized test administered during the experimental period. Indeed, most of the subjects experienced periods of severe emotional distress and depression. There were extreme reactions to the psychological effects during the experiment including self-mutilation (one subject amputated three fingers of his hand with an axe, though the subject was unsure if he had done so intentionally or accidentally).[1] Participants exhibited a preoccupation with food, both during the starvation period and the rehabilitation phase. Sexual interest was drastically reduced and the volunteers showed signs of social withdrawal and isolation. The participants reported a decline in concentration, comprehension and judgment capabilities, although the standardized tests administered showed no actual signs of diminished capacity. There were marked declines in physiological processes indicative of decreases in each subject’s basal metabolic rate (the energy required by the body in a state of rest) and reflected in reduced body temperature, respiration and heart rate. Some of the subjects exhibited edema (swelling) in the extremities, presumably due to the massive quantities of water the participants consumed attempting to fill their stomachs during the starvation period.

Related work

One of the crucial observations of the Minnesota Starvation Experiment discussed by a number of researchers in the nutritional sciences — including Ancel Keys — is that the physical effects of the induced semi-starvation during the study well approximates the conditions experienced by patients afflicted with a range of eating disorders such as anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. Indeed, it has been postulated that many of the profound social and psychological effects of these disorders may actually result from symptoms of undernutrition and that recovery depends critically upon physical renourishment as well as psychological treatment.

- Re: Human Experiment: The Effects of... chirontherainbowbridge

15 y

49,260

This is a reply to # 1,430,817

For some, the fascination was so great that they actually changed occupations after the experiment; three became chefs, and one went into agriculture!

interesting! I don't think you can say this is a compulsive response to "starving", but calorie restriction really removes much of the padding that stands between ourselves and others, and the experience of 'plenty' ( and connectedness to others) that goes along with being a chef is quite delightful. I can see this happening as something 'meant to be' that the padding of weight might have never allowed to open up.I was a chef, some years ago, and was always cooking for dinner parties for my mother, when younger, even cooking the family meal, from the time i was eight and my mother went to work -- and when I fast, I get a newly awakened wish to prepare really good food for others. I feel a heightened sense of its value to others. I'm not consumed (pun intended) with fantasies of food, but I develop a genuine appreciation for really good food. And I tend tend to research things related to growing it, etc. etc. It's partly a slightly wired feeling i think...in a way I'd prefer to meditate for hours, but often don't feel quite 'up to it' physically, while I'm conscious that "I" am not the body; not the head either, but mental faculties work better, and then there's a witnessing part of mind that watches it all, and that i interpret as the *real* me. i digress.

There was a woman in India (probably many of them!), but this one was somewhat famous; she had been a glutton as a child, and once married (still what we would think of a a child) her in-laws made fun of her, for being so -- they taunted her, driving her to the point of declaring that she would prove them wrong, and stop eating altogether. She went to the village priest, or the Indian equivalent, and asked him with great sincerity to help her attain her goal. He apparently took her very seriously, after testing her motivation, and gave her some breathing exercise to do --it's ALL about the breath, ultimately: in that the breath is the only thing one truly "owns" that connects one to the absolute present moment and to all prana...- Anyway. She became a breatharian; until her death. This was proven and well-known throughout the area. The thing is, she continued to cook meals for others. Indeed, she said it was one of her best-loved activities; this caring for others. .

*

about the gum-chewing: rather a carnivorous affair, perhaps; often it allays feelings of aggression: or the ravenous desire for meat, but here's another consideration:

chewing in humans has been discovered to be actively connected to (necessarily) stimulating the parasympathetic nervous system, which controls the release of all sorts of hormones including the 'feel good' ones. For those who are not 'eating from another place' like the breatharians, this is important.

Thus, we are 'made' to chew. Babies suck, which is another kind of chewing, but once teeth appear, they chew, as any nursing mother will tell you! Infirm and the elderly who have no teeth and can only 'gum' soft foods, are no longer experiencing the subtle benefits of chewing --but it may be they are connected to something else: perhaps the fortunate or meritorious ( peaceful or content ) ones are in touch with other sources of "feel-good" hormones. so to speak.

just a few fasting thoughts.these men are alarmingly thin in the none picture. That does look like starvation. Not a bit like fasting (which is all about how the mind interprets the absence -or diminishement- of food. Clearly, they felt deprived. haven't finished reading the piece, but their behaviour mirrors the behaviour of people in concentration camps. Moreso, a lot of people now in old folks' homes ( eps. holocaust survivors ) behave the same way. Taking pieces of cake to their room, hiding them in napkins, rituals of hoarding them. Whisperingly offering them to visitors who might be deemed trustworthy: allies: saying "here, take mine". My partner saw/experienced all this when he visited a place in Montreal, where many of the European Jews reside. He dubbed the general behaviour of the people there "the grey parade". It was quite overwhelming to him. The hard times haven't ended for these people, although all around is abundance. (this was a rather nice retirement facility.)

anyway, interesting reading, Mouse.

Chiron

- Re: Human Experiment: The Effects of... mouseclick

15 y

49,319

This is a reply to # 1,431,070

Your partner was correct, it didn't take me long to find references for that, but they are not in copyable form. You can click here though, that should land you right on top of the page in the Google Preview of Memorial Candles by Dina Wardi and Naomi Goldblum.

I would assume that people starving in the third world would be under the influence of the same mechanism, which seems to be geared towards survival. It probably works well out there, but in this crazy western world of ours it's all gone wrong. SNAFU.

Seems to me like the different behavior is triggered by a nutritional deficiency caused by lack of / incorrect food.

By the way I quickly searched for starvation and third world and found this, which is a book called Beyond Anorexia. Not really third world stuff but the same sort of thing these other articles speak about.

Oh why can't we just buy all this info on a USB stick and plug it into our heads. I am going to give this a rest for a while it takes too much time. But yes, it is fascinating.

- Re: Human Experiment: The Effects of... mouseclick

15 y

49,319